By Lindsay Dade

Coral reefs in the Caribbean are essential resources for food, storm protection, tourism, and recreation. Hard corals, which are the building blocks of coral reefs, are struggling to recover from disturbances like bleaching and coral disease. Some coral restoration practitioners, including organizations like The Nature Conservancy, are seeking to upscale restoration efforts by collecting coral spawn from reefs and rearing them to juveniles in land-based nurseries before outplanting them back onto the reef. This cost-effective technique can greatly enhance their survival as well as promote genetic diversity (Chamberland et al., 2017). The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in St. Croix, US Virgin Islands has a coral propagation operation that they do several times a year during major spawning events. Last month, I traveled to St. Croix to take part in the latest spawning event.

www.nature.org

I am a second year Master’s in Marine and Environmental Science student at the University of the Virgin Islands. Located in St. Thomas, I live just a 20-minute plane ride from St. Croix. I spent three weeks with TNC this summer helping with coral spawning collection, larval rearing, and running experiments for my thesis. The first few days were spent gathering supplies and setting up cleaning stations. Larval husbandry requires serious sterilization; all equipment is typically soaked in diluted bleach, then thiosulfate solution to “de-bleach,” and finally rinsed in fresh water. The species targeted for the September spawning collection were Psuedodiploria strigosa (symmetrical brain coral), Orbicella annularis (boulder star coral), and Orbicella faveolata (mountaneous star coral). All these corals are hermaphroditic spawners, meaning they release gamete bundles that contain both sperm and eggs into the water column for external fertilization. They only spawn a few nights a year, in August and September about 5 days after the full moon. Spawning typically only lasts 30 minutes to an hour. This means restoration practitioners have a small window of time to collect coral spawn. If they miss it, it may be an entire year until the next spawning event. During my stay in St. Croix, I learned that spawning work takes real dedication and attention to detail.

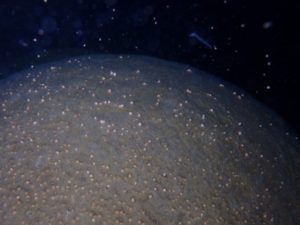

The spawning collection site was located at Deep End Beach, a shallow nearshore reef with large, beautiful O. faveolata and O. annularis colonies. The first night we saw no spawning, but the following night, 6 days after the full moon, we saw gamete bundles floating through the water as soon as we descended. It was a mad dash to get the nets placed over the most promising looking colonies. The nets are shaped like a teepee, with weights on the bottom to anchor it around the coral and a float at the top to keep it vertical. As the gametes float upwards, they condense into a small vial that can be unscrewed from the net, capped, and taken back to the beach for mixing.

Image 1: Pseudodiploria strigosa coral spawning at Deep End Beach.

Photo by Lindsay Dade

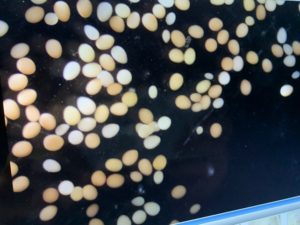

After about 30 minutes of collection, we returned to the beach to mix the gametes and start the fertilization process. Mixing gametes from many different colonies into one concentrated solution helps increase genetic diversity, their chance of fertilization, and keeps them away from predators. We then transported the gamete solution back to the lab to begin the rinsing and culture stage. The unfertilized egg and sperm need to be removed from the solution to keep the fertilized embryos clean and healthy. The clean embryos are then transferred into large containers of sterilized seawater, where they will develop into swimming larvae within the next 12 hours (Randall et al., 2016).

Image 2: Rinsing embryo cultures at TNC. Photo by Lisa Terry.

Image 3: Swimming larvae under a dissection microscope. Photo by Lindsay Dade.

This restoration technique, though labor intensive for a short period of time, can give you a big bang for your buck. Just a few vials of coral gametes can potentially create thousands of juvenile corals that can be placed back onto degraded reefs. Scientists still have much research to do as far as maximizing their settlement and post-settlement survival, but the future of coral restoration using this technique is very promising.

About the Author. Lindsay Dade is a Marine and Environmental Science Graduate student (MMES) at the University of the Virgin Islands. She grew up in Southern Maryland and completed her undergraduate studies at Virginia Wesleyan College in 2016 with a BS in Biology, minoring in Marine Science. Lindsay moved to the Caribbean to work as a Scuba Instructor in 2018, which developed her interest in coral ecology. Her Masters thesis will focus on water quality in relation to larval recruitment of scleractinian corals.

STRONG COASTS is supported by a National Science Foundation Collaborative Research Traineeship (NRT) award (#1735320) led by the University of South Florida (USF) and the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI) to develop a community-engaged training and research program in systems thinking to better manage complex and interconnected food, energy, and water systems in coastal locations. The views expressed here do not reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Comments are closed.