By W. Alex Webb

We often think of museums as the caretakers of history. Large buildings exhibiting what are now exotic artifacts and displays creating windows into worlds that once were. In the past museums were committed to a singular, official history. Over time however, it has become devastatingly clear that no one story can capture the diversity of human experiences. The narratives of who we are depend on our family ties and the myriad of cultural legacies that sustain us. Modern museums engaging people in bringing their pasts to life are then met with a difficult problem: how do you resurrect histories that include everyone?

The National Institute for Culture and History (NICH) in Belize has taken on this contemporary challenge. In her webinar, “What is Heritage Management in Belize”, Sherilyne Jones, a current Strong Coasts Fellow and PhD student of Anthropology at the University of South Florida, details how NICH has created inclusive museums. She would know too. As the once director of Museums of Belize and Staff Archeologist at NICH, then known as the Belize Institute of Archaeology, she was one of few staff charged with the preservation, development, and promotion of Belize’s Cultural Heritage. No easy task considering the many concurrent histories living within the borders of her home country.

Despite being the least densely populated and one of the smallest countries in Central America, Belize is home to a latticework of diverse cultures. Creole, Mestizo, Maya, and Garifuna, among others, comprise a mosaic of peoples maintaining distinct ethnic identifies while living in relative harmony. Traditionally the government of Belize has committed to supporting the heritage of these groups by engaging communities in large scale restoration and conservation projects. Often through the Institute of Archaeology which offers training for locals to become cultural guides for sites adjacent to their homes as a source of income and financial independence. Currently nearly 2/3 of Belize is under protected management with extensive effort having gone into restoring Maya Temples and historical buildings. Preserving and developing Belize’s extensive patchwork of heritages and their many intersections – artifacts and traditions, both contemporary and historical – in an inclusive way required a more innovative approach, however. Rapidly expanding tourism development has brought a constant flow of new people to Belize for work and leisure. In 2018, Belize was the fastest growing tourism destination in the Caribbean. NICH needed a new way to localize and develop cultural preservation.

Houses of Culture

Enter the Houses of Culture, a movement to democratize museums by providing access and support directly to localized communities. Houses of Culture are small scale museums with full time staff providing outreach and education. The aim is to sustain living cultures by embracing contemporary interpretations of traditional ways of doing things. The development of Houses of Culture was based on the Cuban model of ‘Casa de Cultura’ and inspired by a problem identified through the Museum of Belize.

Since 2002, the museum for Belizean culture has been in its most populous city, Belize City. Creating the museum included restoring and renovating “Her Majesty’s Prison”, which had been the city prison from 1857 to 1993. Now, three thousand years of Mayan history and artifacts, displays of colonial life, and presentations of Belize’s many ethnic groups are exhibited in the Museum of Belize. However, despite the museum’s inclusive and representative layout, they were only receiving 3,000 to 5,000 visitors a year in a country of nearly 400,000 people. A widely spread survey of Belizean beliefs about the museum found that most citizens didn’t visit because they thought it was mainly a tourist destination and weren’t sure it was relevant to them. Plus, for residents in the south, the long and winding road to the Belize city in the north could take upwards of 7 hours.

NICH responded with a nuanced approach to cultural preservation by embracing localities. Developing the Houses of Culture was directly tied with the government’s need to decentralize the accessibility of culture and artistic endeavors away from Belize City and make it available to key district towns. The success and challenges each HOC face are a result of the level of autonomy they experience, their ties with the local community, and the financial support they garner for their activities and programs. Since each HOC serves a different community their approaches are dynamic as coordinators work with residents to find projects that are meaningful to them. For instance, the House of Culture in Stann Creek works with Garifuna communities to keep traditions alive through summer camps and festivals. However, activities change from year to year. One summer they might facilitate canoe making courses for children, whereas next summer seine fishing lessons may be more interesting. In relatively short order there was a House of Culture in all seven of Belize’s municipalities. Each one working with communities to celebrate the unique histories and ways of life found there.

Tapestries

On the western edge of Belize is the city of Viejo in the Benque district. Every spring, on the morning of Good Friday, residents wake in the pre-dawn hours to lay beautiful and vibrant sawdust tapestries in the streets. They have been preparing the rugs throughout Santa Semana, or Easter Holy Week, in anticipation of reenactments of the passion play during morning services. For weeks skilled residents have worked with the House of Culture to train youths and others on how to create these renowned temporary tapestries.

Making the tapestries takes planning and a lot of attention to detail. The sawdust is sourced from the mill in Belmopan and then sifted into very, very fine particles. Particles that are then boiled in dye bought from Antigua Guatemala, called añalina dye – the best of its kind I am assured from the staff at Benque’s HOC. The dye dries for over a week as artists design intricate stencils and plan out color combinations. The processions have become a national draw in Belize, a country where many residents hold deep Catholic roots.

Tapestries laid out for Good Friday Passion Play procession. All photos taken from Benque House of Culture Facebook page.

Marimba

Another heritage activity resurrected at the Benque HOC is the Marimba. The Marimba is a percussion instrument in which musicians use a mallet to produce sound from wooden bars. The Marimba has a long history in the region having been declared the national instrument of Guatemala when it became independent in 1821. The initial design included dried gourds as resonators and playing in the seated position. In the mid-19th century, the Marimba evolved to include wooden boxes for resonators and was heightened to be played standing up. By the 20th century an additional chromatic scale was added which mimicked the keys of a piano. American manufacturers eventually began producing a version of the Marimba in the states that was featured in vaudeville and musical acts through the 1970’s including songs by the Rolling Stones, Elton John, and Steely Dan.

When the Benque HOC was established they were in possession of two antique Marimbas. Despite one being on permanent display for several years enthusiasm for the Marimba had dwindled and seemingly no guests and no one on staff knew how to play. But the music still lived within the hands of a few elders in Viejo. With their help the Benque House of Culture secured grant funding for a program to teach youths. Starting with just 14 students and three instructors the program has blossomed with Benque Marimba players becoming mainstays at local and national events.

Students playing Marimba at various local and international ceremonies. All photos taken from Benque House of Culture Facebook page.

Habinahan Wanaragua Jankunu Festival

In the spiritual capital of Garifuna culture, Stann Creek, the HOC has also worked to support long standing traditions. The HOC helps sustain renowned Garifuna drumming and dance through workshops, summer camps, and the annual Habinahan Wanaragua Jankunu Festival (also known as the John Canoe). The Garifuna originate from African and Carib Indians who first gathered in St. Vincent in the southeast Caribbean. Colonial powers forced their movements through South American before settling in Honduras and Belize at the start of the 19th century. The John Canoe festival celebrates Garingu masculinity while satirizing British colonialist. Every year just after Christmas, teams of male dancers and drummers (and occasional female singers) compete in 10-minute intervals wearing brightly colored headpieces, white shirts, pink whitefaced masks, and leggings adorned with loose seashells. The Stann Creek HOC assists in the making of the costumes and as spaces for training dancers and drummers.

Jankunu dancers. Images taken from Stann Creek House of Culture facebook page.

New Economic Opportunities

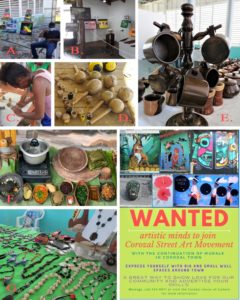

Ornate sawdust tapestries, melodic Marimbas, and lively Wanaragua dance are only a few traditions invigorated by Houses of Culture. In addition to these notable events, houses are also places for learning everyday culture – language, art, and cooking lessons, as examples – and have worked towards creating economic opportunities for residents. In Corozal for instance, the HOC has hosted numerous intensive workshops where people learn to paint, create cornhusk or coconut jewelry, and cornhusk dolls to sell at short-term pop-up markets. Other houses have followed suit by hosting workshops for making palm baskets, bees wax candles, mini drums, and shakers among many other potential consumer goods. In this regard the Houses of Culture are linking old traditions to new opportunities for communities to meet their needs and desires.

HOC Corozal: A) painting, E) wooden cups and pots G) jewelry. HOC Stann Creek: C& D) tiny drums shaker making, Banquitas HOC: layout of ingredients for cooking demonstration to make typical Mayan pork and bean buns dish.

Conclusion

On the Facebook pages of the seven Houses of Culture in Belize, posts are full of free zoom sessions to learn the Garifuna language, listen to local drumming or marimba, calls for activism, fliers of festivals and celebrations, reporting of local politics, and remembrances for people and events gone by. Many of the House’s work has inspired others, with San Ignacio also developing a marimba program and others houses outside of Stann Creek hosting Webinars and events for Garifuna day. The Houses of Culture have moved the museum into the neighborhood, and as a result, old ways are becoming new again. NICH’s innovative approach demonstrates that designing museums for inclusion is not only possible, but that inclusion actually invigorates all our histories.

Above: Strong Coasts Webinar – HERITAGE MANAGEMENT & COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT, with Sherilynne Jones, Strong Coasts Fellow

About the Author. W. Alex Webb is a cultural anthropologist currently interested in the relationship between critical infrastructure transitions and rapid tourism development in the Caribbean. His research emphasizes human-environment relationships, economic anthropology, systems thinking, and the study of science and technology.

Alex’s previous research focused on natural resource management in St Thomas, USVI, tourism development in Southern Utah, and socio-technical systems transitions in Belize. He is currently a student in the Applied Anthropology Ph.D. program at the University of South Florida. He received his BS in Psychology from Westminster College and MS in Marine and Environmental Science from the University of the Virgin Islands.

STRONG COASTS is supported by a National Science Foundation Collaborative Research Traineeship (NRT) award (#1735320) led by the University of South Florida (USF) and the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI) to develop a community-engaged training and research program in systems thinking to better manage complex and interconnected food, energy, and water systems in coastal locations. The views expressed here do not reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Comments are closed.